What We’re Learning

In last week’s post I showed how the work of Massachusetts’ Birth—3rd partnerships is “spilling over” in unexpected and promising ways due to the creation of new social and institutional relationships. These spillovers illustrate how the new relationships that partnerships create can lead to new strategies and build capacity for ongoing improvement. These developments are…

New Article in Kappan Magazine

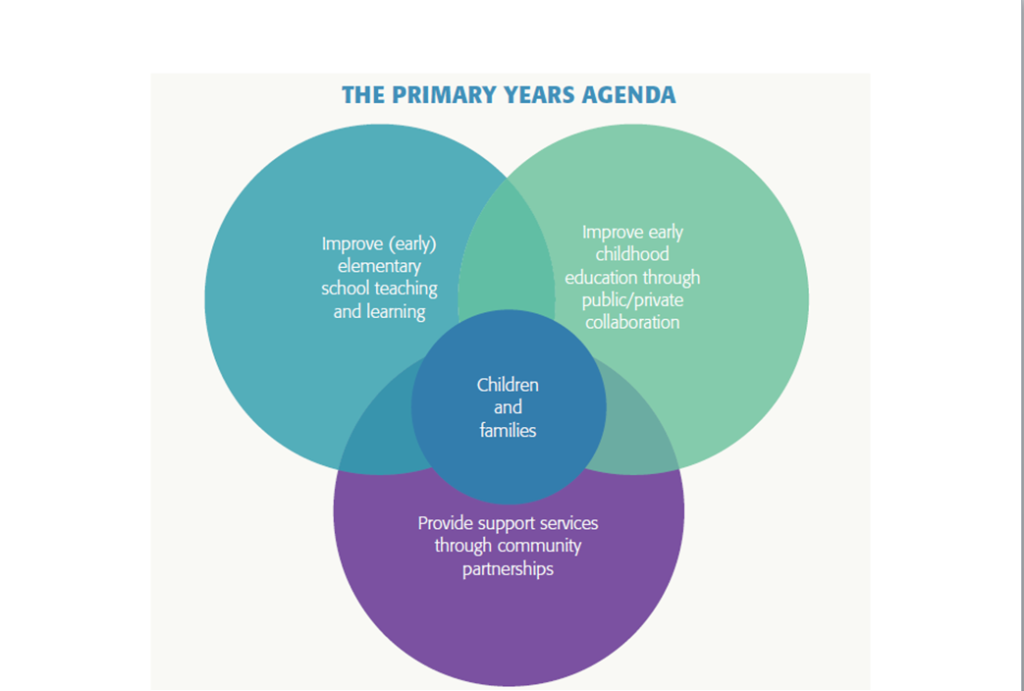

Kappan Magazine has just published an article I wrote , The Primary Years Agenda: Strategies to Guide District Action. I draw on examples from Massachusetts and other states to make the case for three Birth-3rd strategies. These strategies are as relevant to communities as they are to districts. They are intended to help set priorities…

Relationships, Capacity, and Innovation

Innovations often evolve out of a series of what may seem to be minor developments. As a consequence, instead of waiting for disruptive products and technologies, we need to create the conditions for individuals, groups, and organizations to adapt, innovate, and improve all the time. –Thomas Hatch, Innovation at the Core. Principals pick up the…

Teaching a New Curriculum in East Boston (#1)

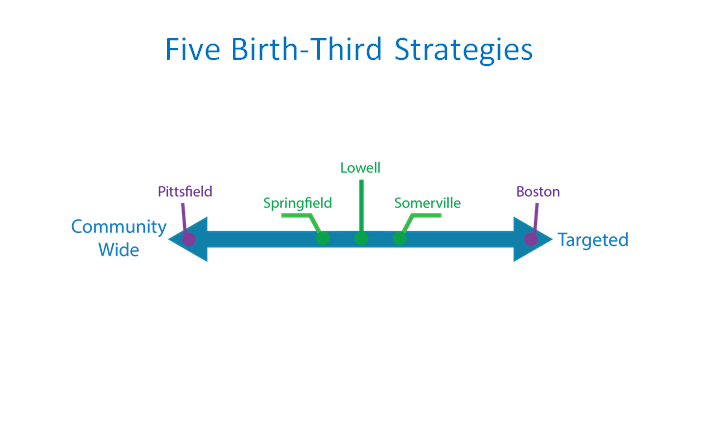

How does classroom practice change as a result of Birth-Third work? How do children, teachers, and leaders experience these changes? Having summarized the strategies of the first five Birth-Third Alignment Partnerships in Massachusetts (Boston, Lowell, Pittsfield, Somerville, and Springfield), I am now posting an occasional series of articles describing the on-the-ground experience of implementing these…

Snapshots of Birth–3rd Strategies in Five Communities

This week I’m posting short bulleted summaries of the core strategies of the first five EEC alignment partnerships, an idea prompted by a helpful conversation with Titus DosRemedios of Strategies for Children last week at an ESE Kindergarten Networking Meeting. These updated summaries may be helpful to the seven new communities coming on board in…

Communities of Practice in Lowell: Supporting Family Child Care and Center-based Providers

As discussed last week, there are multiple entry points for understanding Lowell’s Birth-Third work—the Leadership Alignment Team, the use of the CLASS tool, the emerging school readiness agenda—but a good place to start is with Lowell’s communities of practice. Supporting family childcare providers is a logistically more challenging and less common component of Birth-Third initiatives.[1]…

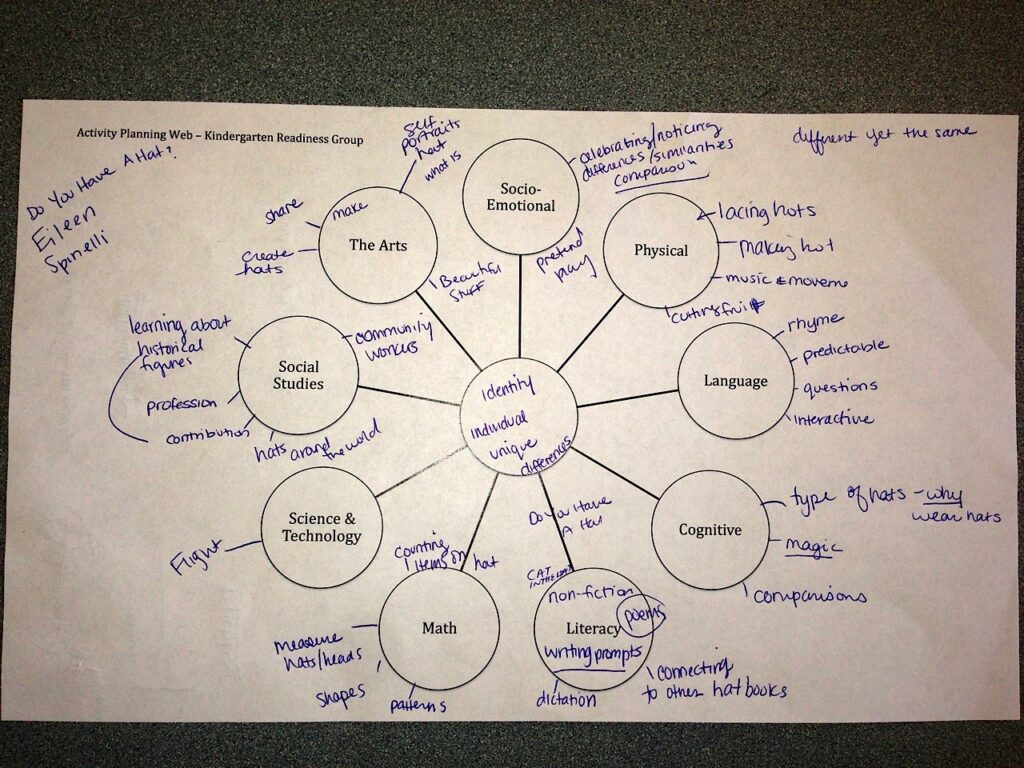

Joint Professional Learning in Somerville and Springfield

Last week’s post described how both Somerville and Springfield have developed professional learning initiatives that bring together prekindergarten and kindergarten educators. The work of Somerville’s Kindergarten Readiness Group and Springfield’s Birth-Third PLC begins to suggest what the content of these workshops can be and what the participants get out of it. These examples also raise a number…

A Community Commitment: Berkshire Priorities and the Pittsfield Promise

The accident of birth is a principal source of inequality in America today. American society is dividing into skilled and unskilled, and the roots of this division lie in early childhood experiences. Kids born into disadvantaged environments are at much greater risk of being unskilled, having low lifetime earnings, and facing a range of personal…

The Boston K1DS Project: Implementing a New Curriculum in Community-based Preschools

On a recent visit to the Paige Academy preschool in the Dorchester neighborhood of Boston, a group of students sit clustered on the rug in front of teacher Sister Paige.[1] Sister Paige leads the students in counting up to 10, with the whole class yelling the even numbers and whispering the odd ones. After a…

“Improbable Scholars” author David Kirp in Somerville

Somerville is graciously sharing a video of David Kirp’s talk about the Union City, NJ success story: https://vimeo.com/89543325. Also see the links below for Kirp’s NYT op-ed and Somerville Mayor Curtatone’s article on the Universal Kindergarten Readiness plan. Here is a link to Somerville’s plan. For additional resources on Union City see PreK-3rd’s Lasting Architecture: Successfully Serving Linguistically and Culturally Diverse Students in Union…