The Case for Improvement and Alignment

Springfield held a Pre-K through Grade 3 conference on November 4 as part of its Birth through Grade Three Alignment Partnership work. The conference brought together senior district leaders, principals, preschool directors and teachers, and representatives from community organizations. The centerpiece of the day was a presentation by Kristie Kauerz, a national leader in the P-3/Birth -Third movement.[1] Kristie was formerly the director of Harvard’s Pre-K-3rd initiative and is currently a research scientist at the University of Washington in Seattle, where she is starting a national P-3 Center.

Kristie’s presentation and the discussion it provoked provide a compelling summary of the research that underlies the Birth through Grade Three movement, an introduction to an important Birth-Third framework, and useful advice and tips based on the experience of communities around the country. Below I share a few highlights.

Brain Development

Kauerz discussed a number of findings from the research on brain development that show the importance of supporting learning and development in children’s first five years. Kauerz shared pictures that illustrate the extraordinarily rapid development of neural connections in the first six years, some of which then atrophy by year 14. According to Kauerz, “What stays are the connections that are reinforced. If we are reinforcing the good things, they stick around.” She emphasized the integrated nature of cognitive, social, and emotional development, saying you can’t tease them apart or do one without the other. While reading proficiency by grade three is an important goal of P-3 efforts, it is one goal of several inter-connected ones, including not only social, emotional, and physical development, but also early mathematical learning. Kauerz notes that preschool math skills have been shown to be an even better predictor of later learning than early literacy skills.

The upshot of the research on brain development: the ability to change brain development and behavior decreases over the lifespan, but happily never bottoms out. We can all keep learning. It is, however, easier, and cheaper for that matter, to influence brain development and behaviors in the early years. “This is our window of opportunity,” says Kauerz.

For helpful visuals on the science of brain development, see Five Numbers to Remember About Early Child Development and Core Concepts in the Science of Early Childhood Development.

Disadvantage and Disparity

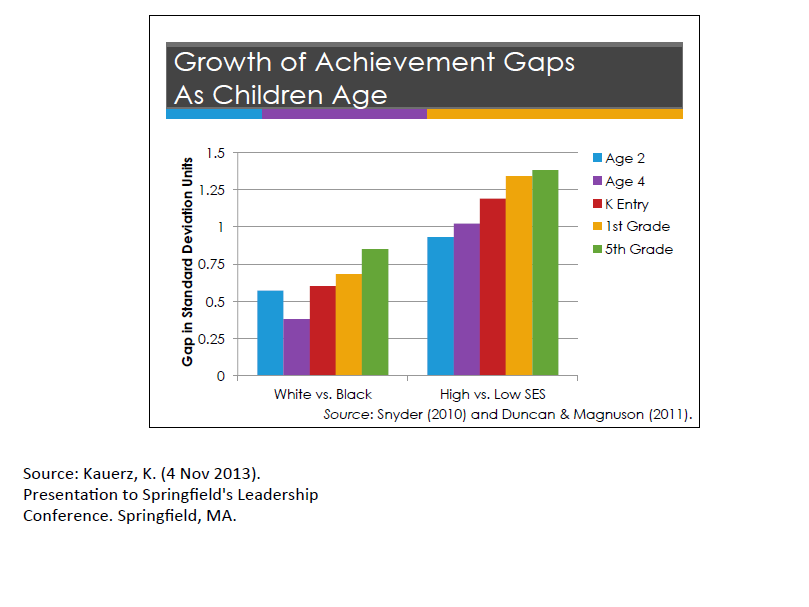

Kauerz points out that there has only been “marginal” improvement in NAEP scores in recent decades and that large achievement gaps remain. Gaps between white and black children are present by age 2 and are larger by kindergarten. Yet it is the gap between low socio-economic and more affluent children that has become the biggest achievement gap. Kauerz shared the graph below, showing evidence of the low-income gap by age 2 and consistently increasing at each step from age 2 to age 4 to kindergarten to first grade to fifth grade. As Kauerz pointed out, “there is work to do at each of these points.”

Quality in Classroom from Prekindergarten through Third Grade: Low Instructional Support

The Center for the Advanced Study of Teaching and Learning at the University of Virginia used the CLASS classroom observation tool to assess quality across the prekindergarten through third grade span in classrooms across the United States. Kauerz emphasized that the study found emotional support to be reasonably good across the spectrum, including in K-3 classrooms, contrary to what some think about early elementary classrooms. Classroom organization was scored slightly lower than emotional support. The big problem, however, was in instructional support, which hovers around 2 on a scale of 7. “This is what we need to be worried about,” says Kauerz. Two-thirds of the students in the study experienced inconsistent instructional support as they progressed from first to third to fifth grade, and one-fifth of students experienced consistently low quality instructional support across these grades.

The P-3 Approach: What If?

Kauerz sees the P-3 approach as a means to address the need to improve learning and development in the first 9 years of life, thereby improving learning for all and reducing gaps. She uses a metaphor to explain her vision of what an aligned P-3 system would look like, comparing toy building blocks to pop beads.

Instead of each silo as a separate building block, pop beads suggest separate pieces, each of which needs independent work but that are connected to each other, yielding a connected, flexible continuum when attached.

Kauerz sets forth as the goals of the P-3 approach three outcomes:

- Developing strong foundational cognitive skills;

- Developing social and emotional competence; and

- Establishing patterns of student engagement in school and learning.

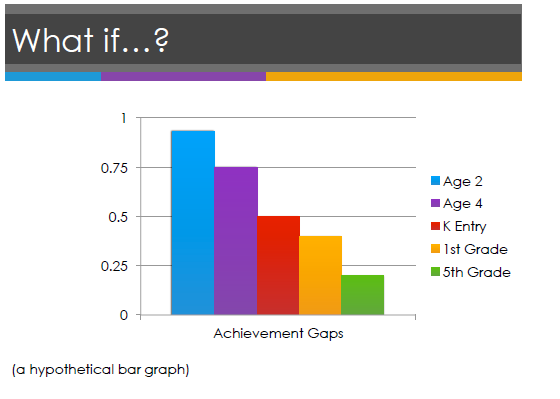

Kauerz shares an inspiring “what if” graph that illustrates a vision of the possibilities successful P-3 work can bring about, a progression of reducing rather than expanding gaps. (For another inspiring graph of the possibility of reducing gaps by “intervening again and again,” see this simulation of the impact of multiple interventions.)

Presentation to Springfield’s Leadership

Conference. Springfield, MA.

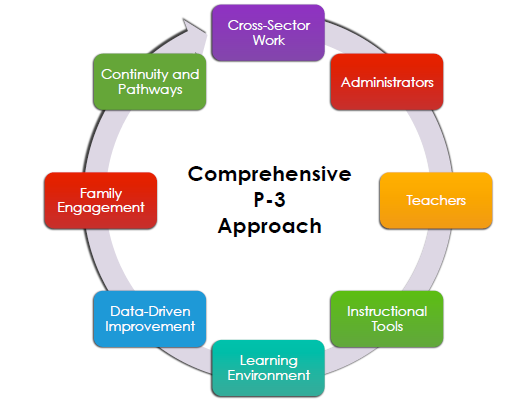

Framework for Planning, Implementing, and Evaluating PreK-3rd Grade Approaches

Kauerz and her colleague Julia Coffman have developed a P-3 Framework that describes the components of P-3 work. This framework includes 8 domains of activity, each fleshed out with a goal, strategies and example indicators. This framework incorporates lessons from communities that have successfully implemented P-3 initiatives, such as Montgomery County, MD and Union City, NJ, as well as input from experts and practitioners in 11 states. (Teams from Holyoke, Springfield, and Worcester provided feedback on the framework at a meeting at Harvard in 2012.)

2013). Presentation to

Springfield’s Leadership

Conference. Springfield, MA.

Kauerz emphasizes that people should not follow the framework like a recipe and instead advises that communities “choose 3-5 things to do really well.” Communities that have successfully done this work had a “laser-like focus” on a small set of goals.

The Work of Implementation

In the discussion that followed her presentation, Kauerz shared the following advice regarding implementing P-3 efforts:

- Priority. Moving beyond superficial implementation requires that leaders make difficult choices about how they are spending money and the initiatives underway in their districts. These choices may require shifting funds from less impactful initiatives and strategically reviewing the accumulation of initiatives to determine what to continue and what to stop.

- Ownership. Kauerz cites instances in which groups have convened to meet and talk about P-3, sometimes on an ongoing basis, but the real work isn’t taking hold. It is critical to build ownership and buy-in among stakeholders, including teachers, if P-3 work is going to have an impact. She cites this example from Chicago in which a partnership started over when it realized it wasn’t making progress.

- Progress-monitoring. Communities cannot wait until “the end” of their initiative to see if they are having an impact. Implementing P-3 requires an extended period of time, but it is critical to monitor progress in an ongoing fashion so that leaders can address problems and make adjustments to ensure that work is leading to improved outcomes for children.

- State Agency Alignment and Misalignment. An audience member noted instances in which districts get conflicting messages from state agencies, whose policies and guidelines are not always aligned. Kauerz mentioned the need for “barrier-busting meetings” in these cases, highlighting the need for multiple state agencies to work collaboratively with districts to address alignment issues.

- False Dichotomies: The Developmentally Appropriate Question. In response to the familiar concern that academic curricula or teaching methods will be “pushed down” from 1 to K to PreK, Kauerz emphasized that P-3 alignment is sometimes hindered by “false dichotomies.” Yes, there are instances of schools in which kindergarten teaching is not developmentally appropriate, and this is an important concern. But our impressions about the quality of teaching and learning in other sectors are not always accurate, as indicated by the high degree of emotional support the University of Virginia study found in K-3 classrooms. Elementary schools use the term differentiated instruction to refer to meeting students where they are, much as early childhood educators use the term “developmentally appropriate.” Whereas early childhood educators talk about the importance of play, K-12 educators are interested in “experiential learning.” As these examples show, vocabulary can become a barrier. Regarding what she regards as false dichotomies, Kauerz asks, “Is your P-3 work an “Us” effort or an “Us vs. Them” effort?”

Two Kristie Kauerz Recommended Books on Successful P-3 Approaches

Leading for Equity: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Montgomery County Public Schools.

[1] A note on terminology: Different terms are used to describe the movement to improve and align education and care from before birth through third grade. Kauerz uses “P-3” to refer to everything before (i.e., “pre-“) school through third grade. Others, including the MA EEC and this blog, use the term Birth through Grade Three (Birth-Third).