“The ultimate goal of a stronger, more seamless care and education continuum is to initiate and sustain a strong foundation for future success by providing effective learning opportunities across the infant-toddler years, preschool ages, and early grades in all settings.” (National Research Council, Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation).[1]

“The broader lesson of our analysis is that social mobility should be tackled at a local level by improving childhood environments.” (Chetty and Hendron, The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility)[2]

The United States is on the cusp of making a historic investment in early care and education (ECE).[3] This investment comes at a moment in time when the pandemic has exposed the fragmented and siloed nature of our early childhood systems in both urban and rural communities. Widespread racial protests have launched a national reckoning with pervasive racial inequities. Also, during the past two years, an important development has been taking place in the ECE world that can help inform our response to these challenges. Twenty-eight states across the United States have been hard at work improving state and local ECE systems, supported by $275 million of Preschool Development Grant Birth through Five (PDG B–5) funds. The aim of these efforts is to improve the quality of early childhood programs and services, including how programs and services work together in a coordinated fashion to best meet the needs of children and families. I suggest that state and local system-building efforts like those supported by PDG B–5 are essential to how we address learning loss in the aftermath of the pandemic, and how, as we expand access to ECE programs, we rebuild better, more equitable systems of care and education.

Over the past six years, my colleagues and I have collaborated with 40 communities in five states that are implementing coherent packages of coordinated strategies to improve outcomes for children and families during the first decade of children’s lives. These communities have established school-community partnerships that improve the quality of teaching and learning, coordinate comprehensive services, and deepen partnerships with families in culturally responsive ways. In effect, these communities are working to create the overall community early childhood environments (through age 10) that ground-breaking research by Raj Chetty and colleagues at Harvard’s Opportunity Insights Project demonstrates is a primary driver of social mobility.[4]

One of these 40 communities, York City, Pennsylvania, is an urban environment in which 95% of students are in households with low incomes and 91% are students of color. The school district and its community partners are knitting together the supports they provide to children and families as they implement a comprehensive plan that includes school hubs that provide supports to families beginning at birth; a city-wide family engagement and parenting campaign; multiple series of school-connected play and learn group sessions for young children at different elementary schools across the city; extensive transition to kindergarten activities for children and families; ongoing joint professional learning for prekindergarten, Head Start, and kindergarten teachers; and a deep, years-long early literacy initiative based on the science of reading.

Another of these communities, Sacopee Valley, is a rural, largely white district in western Maine that serves five small towns. 60% of the student body is eligible for free and/or reduced lunch. In 2018–19, the community came together around a plan that includes a new series of play and learn groups for children ages 0–4 organized by the school district and the public library; a part-time social worker to facilitate comprehensive wrap-around supports; collaborative activities between prekindergarten and kindergarten students; opportunities for prekindergarten and kindergarten teachers to observe each other teach and work together to smooth the transition into kindergarten; the first ever outreach to community-based preschools in the area, which are now using a common student information form for all rising kindergarteners; and work in teacher professional learning communities, including for prekindergarten teachers, on using data and improving literacy and math instruction in the early grades of elementary school.

This post is the first of a 9-part series exploring what we can learn from the 40 communities we have worked with over the past several years, including York City and Sacopee Valley.* I argue that these place-based initiatives are one of the most powerful innovations at our disposal for promoting equity, improving outcomes for children, and strengthening families and communities. Spanning the early childhood—elementary school continuum, these partnerships implement effective, innovative strategies that help all children learn and thrive.

Early Childhood Fundamental Challenge #3

PDG B–5 addresses a critical need, the third of three fundamental ECE challenges the United States must tackle in order to promote equity and improve outcomes for children and families in households with low incomes and families of color. More than ever in recent years, policymakers recognize the importance of increasing access to high-quality ECE (Challenge #1) and understand that doing so sustainably and equitably requires professionalizing the early childhood workforce and improving the compensation of early childhood educators (Challenge #2). Happily, we see this increased understanding, for instance, in Elizabeth Warren’s advocacy and in the White House’s Build Back Better legislation.

The seminal National Research Council report, Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation, marshalled decades of evidence to effectively frame the critical importance of these two fundamental challenges.[5] As such, it functions as an apt marker of the progress that has been made in the last six years in terms of promoting understanding of these issues. Transforming the Workforce, however, also marshalled evidence to effectively frame Challenge #3: the stark contrast between (1) the needs of children and families for high-quality community programs and services that are coordinated and aligned and thus that ensure the continuity of experiences throughout childhood and (2) the pervasive fragmentation that characterizes American ECE systems at the both the state and local levels. Again happily, it is this challenge that PDG B–5 and a wide range of similar cross-sector initiatives are attempting to address.

About the Learning from the First 40 Communities Series

PDG B–5 is part of a broad societal pattern of cross-sector collaboration for education.[6] Examples of related cross-sector initiatives include state-sponsored local early childhood collaboratives in over 20 states,[7] United Way Success by Six partnerships, Early Learning Communities, the By All Means network, a recent Office of Head Start Collaboration Demonstration Project, and perhaps most prominently, cradle-to-career collective impact initiatives such as the Harlem Children’s Zone, Promise Neighborhoods, and StriveTogether.

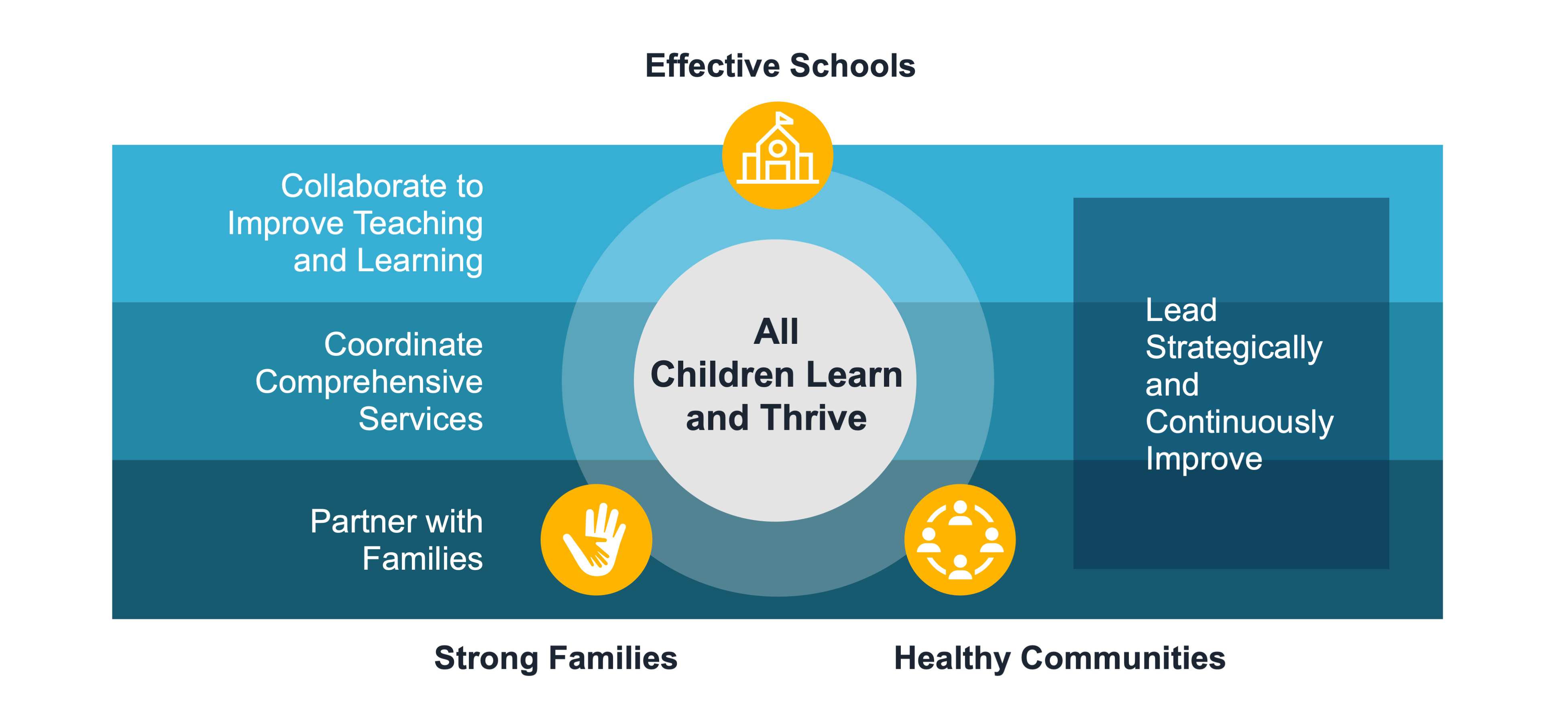

I have collaborated with and studied cross-sector partnerships focused on children and families for many years, and in 2017 I began a research-to-practice study funded by the Heising-Simons Foundation. I interviewed national experts to identify 18 communities that were taking comprehensive approaches to improving programs and services for children and families, interviewed leaders in these communities, and conducted site visits to six communities for a study published in 2019, All Children Learn and Thrive: Building First 10 Schools and Communities.[8] The All Children Learn and Thrive study included case studies of innovative communities as well as a proposed First 10 framework intended to serve as a guide to action for school-community partnerships focused on children and families.

Over the past several years, as we provided technical assistance to early childhood—elementary school partnerships, I have shared the First 10 approach and what I learned from communities such as Boston (MA), Omaha (NE), Multnomah County (OR), Normal (IL), Cincinnati (OH), and others with 32 urban and rural communities in Alabama, Maine, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island, work that is now expanding to Michigan. With a team of colleagues, I have also supported 8 additional communities in Rhode Island in developing and implementing comprehensive Transition to Kindergarten plans, a critical component of First 10 plans. Along with the exemplar communities described in the All Children study, the experience of these roughly 40 communities informs this series of blog posts.

Distinctive Characteristics and Initial Lessons

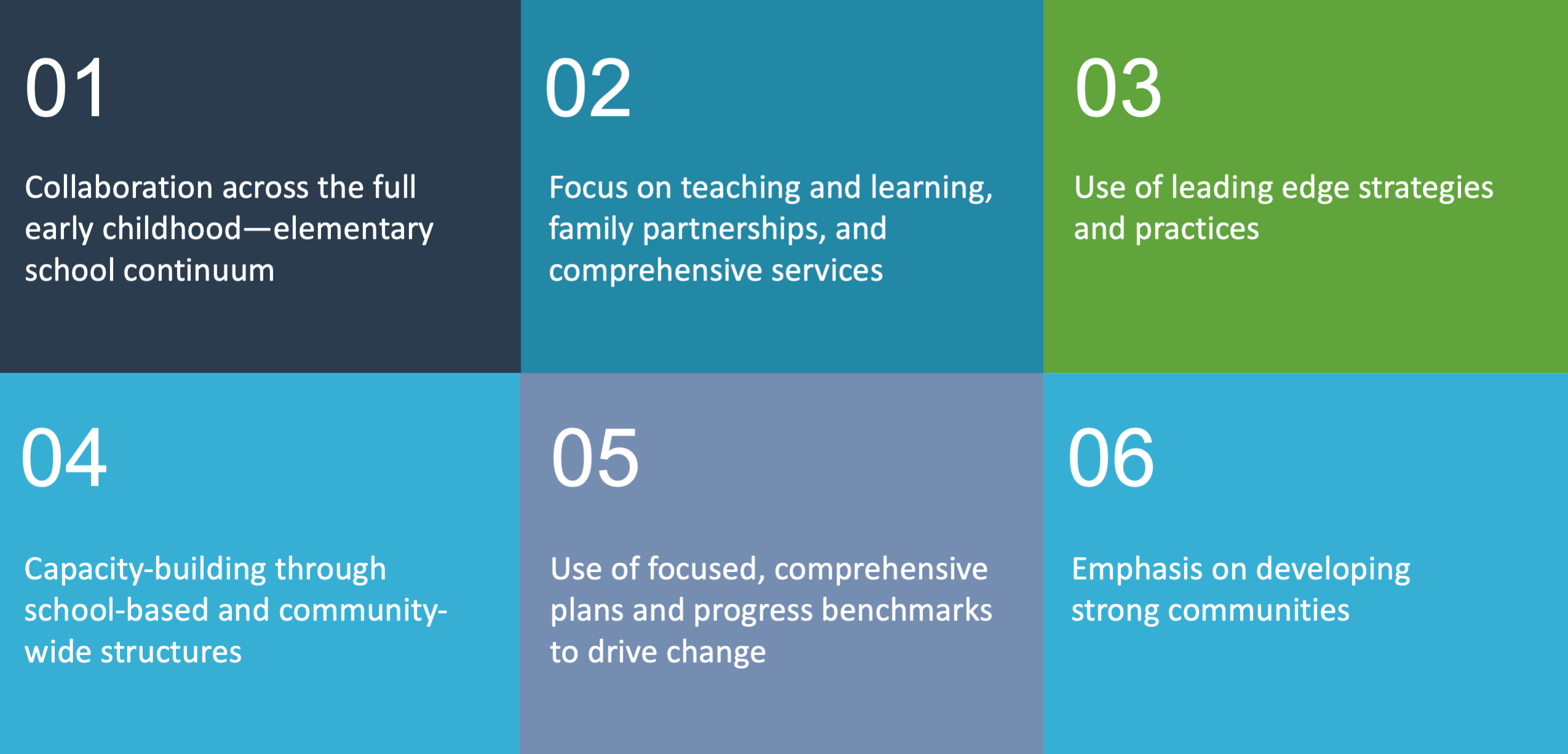

As noted, First 10 schools and communities develop coherent plans that span the full early childhood—elementary school continuum and focus on improving teaching and learning in classrooms, coordinating comprehensive services, and deepening partnerships with families. These plans draw on the strategies and practices pioneered by the exemplar communities in the All Children Learn and Thrive report as well as other communities implementing the First 10 approach. They build capacity to implement strategies effectively as partnerships through both school-based and community-wide structures and by managing plan implementation and using progress benchmarks to drive change. Finally, First 10 partnerships work to strengthen communities while improving outcomes for children and families by explicitly attending to developing trust, social capital among families and organizations, and a service-to-our-community orientation.

Initial lessons learned from the experience of the 40 First 10 and Transition to Kindergarten communities profiled in the forthcoming posts this series include:

1. First 10 partnerships can play a powerful role as a place-based strategy advancing educational and racial equity in urban, rural, and suburban communities. Neighborhoods and communities exert influence on children and families and contribute to educational inequities and racial inequities. First 10 partnerships can help address these inequities by providing targeted resources and supports to communities that have fewer resources, increasing access to effective learning approaches, increasing access to comprehensive services, building strong relationships with families, and promoting family wellness and leadership.[9]

2. Communities can establish First 10 partnerships and begin implementing effective strategies with relatively small amounts of seed funding. In doing so, they build a platform and the capacity for ongoing collaboration. Fully addressing the challenge of improving quality and alignment will require additional funding as the movement continues to gain momentum.

3. Creating school-community partnerships that span the early childhood—elementary school continuum makes possible a range of promising strategies that would not be feasible if implemented only within early childhood programs or only within the K–12 system. These include:

- Shared community-wide approaches to supporting families and common community-wide parenting campaigns

- Comprehensive transition to kindergarten plans that include ongoing collaboration between ECE and kindergarten educators on teaching and learning in classrooms

- Community-wide approaches to improving social-emotional learning, literacy, and math in early grades’ classrooms that include alignment across district, Head Start, and community-based classrooms

- Structural innovations such as First 10 community school hubs (discussed in Post #3) and school-connected play and learn groups (Post #5)

- The potential for even deeper collaborat ion between larger nonprofits and school districts as well as for more ambitious strategies, including home visiting system-building and communities of practice for family childcare providers and early childhood centers

The Learning from the First 40 series includes the following posts:

- Communities Take Action for Children and Families: Learning from the First 40 Communities (this post)

- Promoting Educational and Racial Equity through Cross-Sector Partnerships for Children and Families

- Getting Started with First 10: Community Partnerships, School Hubs, and Work Currently Underway

- Strategy #1: Collaborate to Improve Teaching and Learning

- Strategy #2: Coordinate Comprehensive Services

- Strategy #3: Deepen Partnerships with Families in Culturally-Responsive Ways

- Lead Strategically and Continuously Improve

- The Role of States, Regions, and Networks

- Conclusions and Initial Lessons

Check back in two weeks for Post #2: Promoting Educational and Racial Equity through Cross-Sector Partnerships for Children and Families.

*I am grateful to the following reviewers for their valuable feedback on this blog post series: Laura Bornfreund, Kim Elliott, Rolf Grafwallner, Isabelle Hau, Jennifer LoCasale-Crouch, Joan Lombardi, Caitlin O’Connor, and Deborah Stipek. Special thanks to Kim Elliott for her thoughtful editing support.

[1] National Research Council, Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2015), 211.

[2] Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendron, The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility: Childhood Exposure Effects and County-Level Estimates [Executive Summary] (Cambridge, MA Harvard University, 2015), 6.

[3] ECE includes Head Start programs, state-funded prekindergarten programs, community-based preschools, and family childcare providers.

[4] “Neighborhoods Matter: Children’s lives are shaped by the neighborhood they grow up in,” Opportunity Insights, Harvard University accessed April 6, 2021, https://opportunityinsights.org/neighborhoods/.

[5] National Research Council, Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation.

[6] Jeffrey R. Henig et al., Putting collective impact in context: A review of the literature on local cross-sector collaboration to improve education (New York, NY: Teachers College, Columbia University, Department of Education Policy and Social Analysis, 2015).

[7] Gerry Cobb and Karen Ponder, The Nuts and Bolts of Building Early Childhood Systems through State/Local Initiatives (Build Initiative, 2014).

[8] David Jacobson, All Children Learn and Thrive: Building First 10 Schools and Communities (Waltham, MA: Education Development Center, 2019).

[9] Erin Hardy et al., Advancing Racial Equity through Neighborhood-Informed Early Childhood Policies: A Research and Policy Review (Waltham, MA: diversitydatakids.org, 2021); S. Meek et al., Start With Equity: 14 Priorities To Dismantle Systemic Racism in Early Care and Education (The Children’s Equity Project, 2020), https://childandfamilysuccess.asu.edu/cep; “Neighborhoods Matter: Children’s lives are shaped by the neighborhood they grow up in.”