This post updates a theory of action and 7 associated principles that I first posted last year. I’ve revised a few of the principles, and the principles line up with the graphics much more clearly now. I also draw attention to three distinctive features of the theory of action. According to the blogging platform Medium, this post is a 12-minute read. See this page for an overview of the core ideas. Many thanks to friends and colleagues for all the helpful feedback. ¹

Over the last 10 years, research, policy, and expert opinion have converged on the idea that addressing achievement gaps requires a comprehensive focus on the first 8-9 years of life, beginning with prenatal care and continuing with high-quality supports through third grade (P-3). The goal of this work is to improve the teaching and learning of cognitive and academic skills while deepening supports for physical and mental health, social-emotional learning, and family partnerships.

Community partnerships of elementary schools, community-based preschools, and other organizations serving young children and their families have great potential for achieving this goal and addressing achievement gaps. When these organizations take concerted action around a common set of goals and strategies, they are among the most effective and powerful ways of improving educational outcomes for lower income children.

Quality Within, Continuity Across

In order for early childhood education and early elementary school to be most effective, communities need to address two obstacles. The quality of both early childhood and early elementary education is highly inconsistent, and the mixed delivery system is characterized by a high degree of fragmentation. Addressing these twin obstacles–inconsistent quality within organizations and fragmentation across organizations–requires a collective response on the part of communities, efforts that require state and federal support as well.

Communities need to raise the quality of education and care in the various community-based organizations and public elementary schools that serve young children and their families in their locale; they also need to create meaningful linkages that align and coordinate the work of these organizations. Developing this capacity requires partnerships of schools, community organizations and families focused on quality and continuity–what I call P-3 Community Partnerships.

Theory of Action and 7 Principles

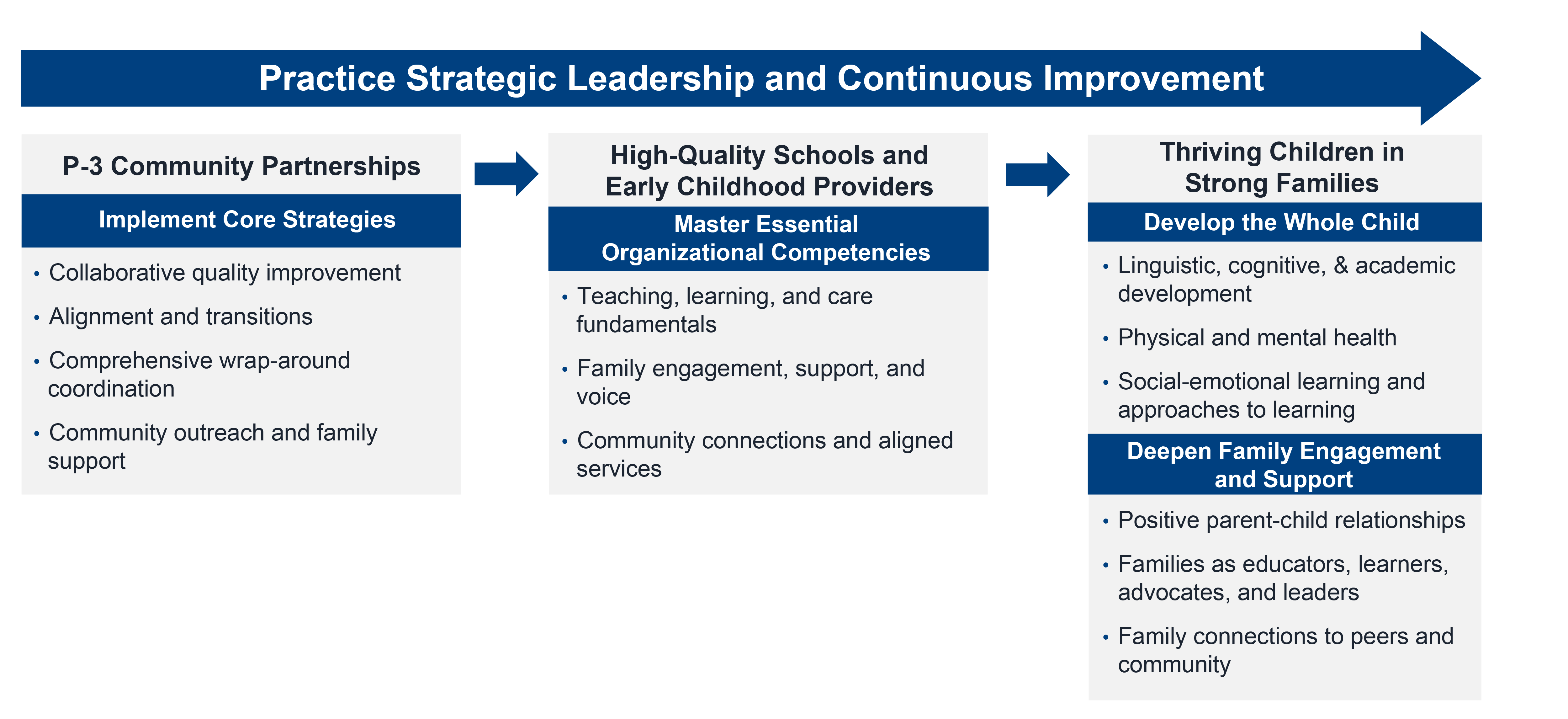

The graphic above shows how P-3 Partnerships can best support schools and community-based organizations in improving early learning outcomes. It is one of two graphics that together illustrate a theory of action for P-3 Partnerships. ²

A theory of action tells a story about how a series of strategies are expected to lead to positive outcomes, creating what some have called a “causal story line.” In effect, a theory of action is a hypothesis about a series of activities that lead to outcomes and that can be tested and improved over time in light of experience.

As depicted in the graphic above, P-3 Partnerships implement a set of strategies to support P-3 organizations in attaining high levels of quality. Through these strategies, P-3 Partnerships help their member organizations master a set of essential organizational competencies. In a second graphic, below, the theory of action further outlines how states and communities can support these efforts, all in service of thriving children and families.

Most theories of action take the form of an if-then statement. The if-then statement that the graphic above depicts goes as follows:

- If P-3 partnerships implement a set of core strategies to build the capacity of their member organizations, and,

- if, with this support, P-3 organizations master a set of essential organizational competencies and thus attain high levels of organizational quality,

- then children will thrive in strong families.

The principles below, listed in the dark blue boxes in the two graphics, explain the theory of action in more detail.

Preview: Distinctive Features. As the principles described below make clear, the P-3 theory of action places significant weight on several distinctive features. First, it emphasizes capacity-building as the central role of P-3 Partnerships. P-3 Partnerships support their member elementary schools, preschools, and other early childhood organizations in mastering a few essential organizational competencies that drive organizational quality and alignment. This capacity-building is focused not only on leaders and teachers but on organizational structures and processes as well—the way the organization “does business” and organizes itself to meet its goals.

Further, in response to well-documented needs, the theory prioritizes both the vertical alignment of services as children develop from infants and toddlers to preschoolers to elementary school students as well as the horizontal alignment of wrap-around services at each stage of development. Finally, the P-3 theory of action is fundamentally place-based in that it highlights the potential of P-3 Partnerships to improve quality and alignment within defined geographic areas so that neighborhoods and communities can benefit from a concentration of mutually-reinforcing programs, services, and relationships. The place-based potential of P-3 Partnerships has implications both for the design of services and programs as well as the development of relationships with broader cradle-to-career and collective impact initiatives. These distinctive features are discussed further in the principles below.

7 Principles of Effective P-3 Community Partnerships

The aim of the theory of action is to provide guidance for P-3 Partnerships as they design and implement their strategies. The theory of actions also provides a structure for collective learning–both within and across communities–about how best to implement these strategies.

- Implement Whole Child Development Systematically

American educators have long valued whole child approaches. Interest in whole child development has increased significantly in recent years among both liberal and conservative policymakers and practitioners in response to mounting research findings. Supporting whole child development presents the challenge of improving the teaching and learning of cognitive, linguistic, and academic skills in the early years while simultaneously deepening social-emotional and health supports. Much work remains improving cognitive and academic instruction, and typically physical and mental health and social-emotional learning have not been integrated into the core work of educational systems. Thus implementation has been overwhelmingly superficial and fragmented. P-3 Partnerships can help build the capacity of their member organizations to implement whole child approaches systematically through the strategies described below.

- Deepen Family Engagement and Support

In the same way that we are at a turning point on the importance of whole child development, we are also at a turning point regarding engaging and supporting families. Family researchers on both the left and right agree that economic and social changes are taking a significant toll on low-income American families. These changes are leading to more family instability, which has negative consequences for young children. This trend makes improving early learning and development more challenging, but it also makes the work of engaging, partnering with, and supporting families all the more important.

The family engagement outcomes of the well-known and highly-respected Head Start Parent, Family, and Community Engagement Framework provide a clear set of goals for P-3 organizations. These goals have been affirmed in the recent joint statement on family engagement by the U.S. Departments of Education (DOE) and Health and Human Services (HHS). The joint statement reviews the research that supports the Head Start outcomes and lays out family engagement principles that span early childhood and K-12 education. For the P-3 theory of action, I summarize and consolidate the Head Start goals as 1) Positive Parent-Child Relationships, 2) Families as Educators, Learners, Advocates, and Leaders, and 3) Family Connections to Peers and Community. These goals in turn help support the ultimate goal of P-3 Partnerships, Thriving Children in Strong Families.

In order to attain these goals, communities need to improve coordination between schools, preschools, and other community-based organizations and scale up effective family support and parenting programs. The widely-used Strengthening Families framework is a useful guide here and can serve as a resource for community-wide efforts. The framework is based on five evidence-based “protective factors” that support strong families: parental resilience, social connections, concrete support in times of need, knowledge of parenting and child development, and the social and emotional competence of children.

- Master Essential Organizational Competencies

A seminal study of elementary schools in Chicago found that the schools that were highly successful with low-income children had mastered a number of essential organizational competencies that include teaching and learning fundamentals, family engagement, and community connections. In fact, only schools that successfully implemented all of these dimensions of education and care were successful (hence the study authors’ use of the term “essential”). Research on quality in early childhood education supports these findings as well. Thus the defining role of P-3 partnerships is to build the capacity of P-3 organizations to master these essential organizational competencies. These competencies, described below, can serve as a common focus and a common language for collective, community-wide capacity-building.

- Teaching, Learning, and Care Fundamentals. Developing the organizational capacity to sustain high-quality teaching, learning, and care requires well-defined supports (e.g., curricula, formative assessments, agreed-upon instructional approaches, and effective use of data), professional capacity (recruitment, retention, and collaborative professional learning) and student-centered learning climate and environments.

- Family Partnerships, Support, and Social Ties. Building partnerships with families that support engagement in child learning and development and the cultivation of positive social ties.

- Community Connections and Aligned Services. Ensuring continuity and comprehensiveness in the services that children and families experience requires coordination across schools, preschools, and community-based social service agencies and positive relationships between educational institutions and the communities in which they are located.

- Build Capacity through Core Partnership Strategies

Mastering the essential organizational competencies is challenging work that requires support from partners. Strategically-focused partnerships can play a critical role in building capacity around the competencies in elementary schools, preschools, and other P-3 organizations. Not only can partnerships help make connections between the different P-3 organizations in a neighborhood or community, but they can also create efficient arrangements for delivering high-quality coaching and professional learning on common topics within a common framework (e.g., early literacy, social-emotional learning, and developing partnerships with families).

Happily many such partnerships are emerging across the country, and many of them have proven to be very effective. Some, like those in Union City, NJ and Montgomery County, MD, have focused on P-3 alignment, coaching, and professional learning. Others focus on horizontal comprehensive wrap-around services (e.g., Cincinnati, OH and Portland, OR), and yet others focus on addressing adverse childhood experiences (e.g., rural Washington State). Building on the research on these partnerships, the P-3 Theory of Action suggests that P-3 partnerships implement several core strategies—perhaps phased-in over time—to build capacity in their member organizations around the essential competencies.

The first capacity-building strategy for P-3 organizations is to collaborate on improving quality. This may entail preschool and kindergarten teachers participating in joint professional development, a common program of professional development and coaching to support a group of preschools, or a community of practice for groups of family childcare providers or home visitors. Another core strategy is to improve transitions and alignment across P-3 organizations, especially preschools and elementary schools, by aligning standards, curricula, and assessments and developing transition plans. P-3 Partnerships are also well-positioned to help coordinate comprehensive wrap-around services such as health care referrals, early childhood mental health consultation, and out-of-school time connections. Finally, many P-3 Partnerships coordinate community-wide outreach campaigns (e.g., regarding early literacy or adverse childhood experiences) and family supports such as child screening initiatives, parenting education programs, and parent cafes.

These strategies follow the recommendation of the highly-regarded Institutes of Medicine report, Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth through Age 8. Assessing the fragmented state of the mixed delivery system in most communities, the report marshals a great deal of evidence to suggest that P-3 partnerships promote both vertical (across the age span) and horizontal (wrap-around services at a given stage of development) continuity for young children.

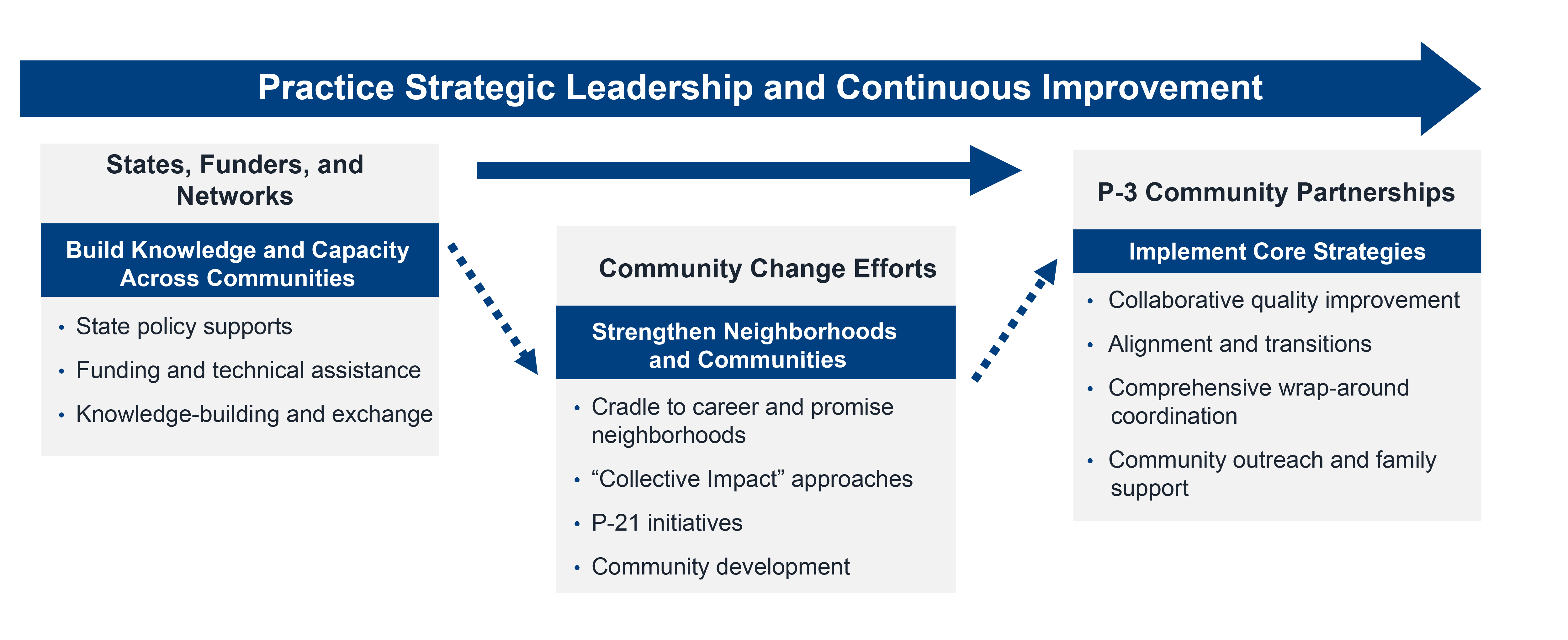

The second part of the theory of change, illustrated in the graphic below, focuses on how states, other funders, and communities can support P-3 Partnerships and on how P-3 Partnerships can contribute to broader community development initiatives.

- Strengthen Neighborhoods and Communities

Liberals and conservatives often agree on the importance of local capacity-building and strengthening neighborhoods and communities. P-3 Community Partnerships are part of a broader trend towards place-based partnerships that aim to improve educational outcomes and strengthen neighborhoods and communities. Inspired by the Harlem Children’s Zone and similar initiatives, place-based cradle-to-career partnerships of schools and social service agencies are premised on the “both/and” idea that addressing poverty requires improving schools and improving social services. It is with this both/and quality in mind that a recent Wallace Foundation report suggests that such partnerships are “moving beyond” the debate between conservative-leaning proponents of “no excuses” school reforms and liberal-leaning “bigger, bolder” advocates for increased social services.

Cradle-to-career initiatives bring together education and social services agencies in concerted efforts to produce measurable outcomes within defined geographic areas through a coherent package of comprehensive strategies. These initiatives often draw on the Collective Impact methodology, which emphasizes shared measures to guide “mutually-reinforcing activities” across partners in service towards a common vision. Further, motivated by a similar impulse towards comprehensiveness, community economic development organizations are increasingly looking to combine investments in early childhood and school reform with place-based initiatives that include housing, economic development, and workforce development initiatives as well.

P-3 Community Partnerships can be more explicitly place-based by designing strategies that have mutually-reinforcing impacts within defined geographic areas (e.g., the neighborhood around an elementary school). Conversely, communities that have developed cradle-to-career and community development initiatives can draw on the growing knowledge base on P-3 improvement and include P-3 Community Partnerships as central components of their work. P-3 Partnerships can both benefit from and support broader place-based initiatives. In doing so, they can contribute to more encompassing initiatives that provide crucial supports beyond third grade and that link to complementary initiatives involving housing and economic and workforce development.

Place-based cradle-to-career initiatives do not exist in all communities (hence the dotted lines in the 2nd graphic), but where they do, they can work hand-in-hand with P-3 Partnerships.

- Build Knowledge and Capacity across Communities

Supporting P-3 organizations in mastering the essential competencies through the core functions of P-3 Partnerships has great potential. Yet in order to build the capacity to play this critical role, communities will need support from states, funders, and networks of communities. P-3 state policies regarding standards, formative assessments, leadership development, and workforce development are crucial supports for effective P-3 practice in the field, as are targeted grant programs to support local P-3 capacity. (See Building State P-3 Systems: Learning from Leading States and this related post at Preschools Matter Today.)

Further, ambitious cross-sector initiatives have much greater chances of success if they are supported in developing leadership and organizational capacity and if they are able to access practical knowledge about strategy, program implementation, and available resources. Internationally, many countries and provinces have had significant success supporting education reform through regional and state networks, and a number of states in the U.S. have begun to develop innovative support systems for P-3 in particular.

- Practice Strategic Leadership and Data-Driven Continuous Improvement

Leadership and continuous improvement are integral to P-3 improvement at every stage of the theory of change. The Chicago study of effective elementary schools serving low-income students found that leadership acted as the driver of all the essential organizational competencies successful schools developed, a finding that is consistent with research on early childhood organizations as well. Leadership is equally critical at the partnership, community, and state levels. At all of these levels, leaders will be aided in building the capacities specified in the theory of action by developing focused strategic plans and managing these plans carefully: using data to monitor progress, adjust strategies, solve problems, and improve coordination.

An Emerging Boundary-Spanning Consensus

Education policy, like American politics in general, is highly polarized. Yet among the many substantive areas of disagreement, a consensus has emerged around the education priorities that animate the P-3 Partnership Theory of Action: supporting whole child development, engaging and supporting families, strengthening neighborhoods and communities, and starting early by improving quality and coordination throughout the P-3 continuum. I discuss the consensus around these priorities and the implications for P-3 Partnerships in a forthcoming Education Week Commentary. Check back for a link to the Commentary soon.

¹ In particular, I’d like to thank the following for their invaluable suggestions: Laura Bornfreund, Elliott Regenstein, Angela Farwig, Kyrsten Emanuel, Lisa Hood, Karen Yarbrough, Chris Maxwell, Martha Moorehouse, Rebecca Gomez, Sara Vecchiotti, Naomie Macena, Joan Wasser Gish, Titus DosRemedios, Keri-Nicole Dillman, Sarah Fiarman, Rob Ramsdell, Joanne Brady, and Pat Fahey. Special thanks to Sarah Fiarman for in-depth conceptual and editorial support on this and related over several years.

² The model is intended to build on and complement the Framework for Planning, Implementing, and Evaluating PreK-3rd Approaches, drawing on the growing knowledge base regarding P-3 partnership efforts, early childhood education and care, school reform, family engagement, and community partnerships.